Review by Nick Gevers

(This review first appeared in Interzone, 11/2000)

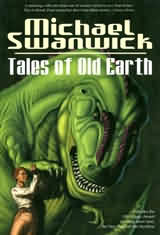

Tales of Old Earth

Frog Ltd./Tachyon (USA), 2000

Even in a year of outstanding SF and Fantasy collections, Michael Swanwick's Tales of Old Earth is a nonpareil. The nineteen stories gathered here, all but one dating from the 1990s, are restless, cogent, sardonic, precise, superb examples of narrative craftsmanship in miniature, each expressing its moral or ironic point with great style and marvellous economy.

The idiom of the SF genre has rarely been employed with such fluent intelligence as here; yet Old Earth, the Earth of the present and the past, is as much this book's subject as is its whirling dance of hazarded futures.

As an example of Swanwick’s technique, consider "The Mask", at a mere six pages the shortest piece in Tales Of Old Earth. The ornate flamboyance of the past is very much present: masked aristocrats walk the Rialto of Venice, sexual and political intrigue is everywhere, archaic creeds of duplicity and honour are implicitly invoked. But the technologies that enable this scenario are of the future, as are speculative incongruities: since when do titled personages head "Communes"? And then the amorous interlude of Lady Nakashima and a defecting engineer from Green Hamburg—the Renaissance fornicating with a cyberpunk future—is focused like a sudden concatenation of lenses on the myopia and pecadilloes of the corporate present, in a brief and brusque but resounding punchline. A vivid marriage of tenses (their styles, sensibilities, and characteristic paraphernalias wedded with seamless mischief) segues into an argument of immense forceful pertinence: postmodern moralism at its most acute.

Just as illustrative, and even more effective, is "The Wisdom of Old Earth" (eleven pages). Here Swanwick takes one of the great intellectual fallacies of the past, the notion that evolution is an upward movement, a teleology conferring genetic superiority on its beneficiaries, implants it in the mind of an ambitious woman of a conspicuously devolved far future, and finally springs a cruel trap, one that condemns her as an evolutionary dead end and dismisses crushingly any contemporary suppositions of the inferiority of others. To read such pieces is to learn just how devastating a form of narrative rhetoric the short story can be, and not one of the entries in Tales of Old Earth fails to drive the lesson home.

However far he ranges in space and time, Swanwick always has the present in his crosshairs. "The Very Pulse of the Machine" (a Hugo Award winner in 1999) may postulate that a moon is a machine, and "Microcosmic Dog" (a clever homage to a similarly-titled classic by Theodore Sturgeon) may make antic play with geometries of scale in reconceiving New York as a solipsist’s shell, but both address a painfully immediate dilemma of Faith. "Radiant Doors" may appropriate the manner of the hard-boiled SF yarn and colonise a near future with a more remote one, but it addresses most centrally the folly of expecting the worst. "Mother Grasshopper" is utterly whimsical in depicting starshiploads of humans settling a gargantuan insect of space, with Ray Bradbury’s folksiness in the background and his eerie morbidity in the foreground, but the implication that we are vermin is inescapable, as is the greater perspective that we are vermin even to those we consider vermin ourselves. "Wild Minds" is about a future of posthuman modification, but it sets out limits on that process that are timeless rather than speculative.

Rather like James Tiptree in her Seventies heyday, Swanwick has a particular grasp of the fictional modes of Death. "The Dead" turns industrial-scale resurrection into a revolutionary nightmare for the elite (as in Ian McDonald’s Necroville (1994)), but echoes also "The Dead" by James Joyce in its final limpid universality. In "Radio Waves", the recently deceased are fading signals of themselves, riding electrical cables, resisting galvanic predators, and contemplating fearfully the empyrean whose background radiation they ineluctably will join; but they are also seeking authentic psychological closure. "North of Diddy-Wah-Diddy" features the train that transports the damned to Hell and Hell’s marginally less infernal suburbs; but its journey is also one on the Underground Railroad, to liberation and beyond. In contrast, the bleakly comic dialogue of "Midnight Express" occurs between two rail passengers in Faerie, one of whom is the certain corrupter and nemesis of the other; and "The Raggle Taggle Gypsy-O", a story original to this collection, boisterously considers, amidst its riffs on Roger Zelazny, E. R. Eddison, Philip Jose Farmer, and many others, the paradox that immortality is only possible through the memories of those left behind when we perish…

Other tales are less funereal, but at least as scathingly forceful. "In Concert" exploits a dubious pun ("Lennonism", in essence) to suggest just how much Communism and rock-‘n-roll eventually disappointed their followers; "Ancient Engines" is an Asimovian reflection on a singular and singularly dispiriting paradox of technology; and "Walking Out", after a mild joke at the expense of Terry Bisson, explores a tragic extreme of claustrophobia. "Scherzo With Tyrannosaur" and "Riding the Giganotosaur" are tantalising sketches for Swanwick’s forthcoming novel The Jaws Of Time (title decidedly tentative), weaving respectively a very stark web of time paradoxes and a portrait of a corporate buccaneer who learns humility amidst the slapstick savagery of the Cretaceous. And long evolutionary perspectives are proffered by a couple’s antique refrigerator in "Ice Age", an early story whose whimsical manner slyly imparts the vertigo such vistas must induce.

The greatest highlight, the most intricately structured and intellectually provocative item in Tales of Old Earth, may well be "The Changeling’s Tale", which thus deserves a special mention. This short venture into full-blown Fantasy is avowedly a tribute to Tolkien, but its recursive tracings of memory and temptation act to sour the Tolkienian formula, deriding its excesses of length and sentiment, dismissing its moral pretensions, demanding in condign mood that Fantasy address at last the urgencies of the real. The eighteen pages of "The Changeling’s Tale" say more than the multiple volumes of any Tolkienian epic, and indict them as thieves of time, and squanderers of paper.

Tales of Old Earth may well emerge as the best collection

of 2000, perhaps the year’s best SF book in any category. It

is exhilaratingly disturbing, a Pandora’s Box of nineteen inestimable

gems.